Why English Majors are Better at Grasping the Universe than Physicists (or Attorneys)

- John S. Koehler

- Aug 19, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 21, 2023

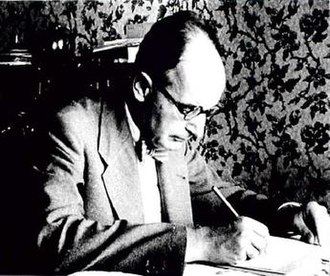

The two gentleman here are Kurt Grelling and Leonard Nelson, and they are responsible for many undergraduate students of mathematics and logic having sleepless nights as they contemplate the significance of the Grelling–Nelson paradox. Just what is the Grelling–Nelson paradox, you ask? Well, if you value your beauty sleep, and unless you are an English Major (the academic kind, not the military kind) DO NOT READ FURTHER!

Oh, you are still here? OK. So, either you are an English Major, or you truly enjoy insomnia.

In its simplest form, the Grelling–Nelson paradox involves the definition of two words, "autological" and "heterological."

An autological word is "a word that describes a set of things that includes the word itself." For example, anapæst, which means a poetic metric that is two short or unstressed syllables followed by a long or stressed syllable, is itself an anapæst because it has two short syllables followed by a long one. Velveteen is also an anapæst. Lord Byron's “The Destruction of Sennacherib” is written in anapæstic meter.

Heterological is the antonym of autological, meaning a word that does not describe itself. For example, monosyllabic is heterological because it has five syllables, not one (however, pentasyllabic, meaning having five syllables, is autological -- unless you mispronounce it "pent-a- slab-ic").

But can one say with certainty that all words must be autological or heterological? It would seem so, because a word either describes a set it belongs to or it doesn't. QED.

Similarly, it seems apparent that autological must be autological, because words that describe sets to which they belong are autological, and thus a word that that describes that set of words that describe themselves must itself be a part of that set, right? And, since heterological is the antonym of autological, it cannot be autological. Except . . .

Heterological cannot be heterological either, because if it is, then it is autological. In fact, heterlogical does not fit into either category, because whichever category you choose to place it in, you create a contradiction, viz.:

Is "heterological" a heterological word?

no → "heterological" is autological → "heterological" describes itself → "heterological" is heterological, contradiction

yes → "heterological" is heterological → "heterological" does not describe itself → "heterological" is not heterological, contradiction

Now that might be enough to blow your mind, but here is the real paradox . . . autological is autological, as we already demonstrated, but it is ALSO heterological. How can this be? Because our original proof that autological was autological, we presumed that it fit in that category, and so it did.

But if we start from the opposite proposition by stating that "autological is not a word that describes a set of words of which it was a member," then autological is heterological, disproving the original proposition, and rendering autological heterological.

In other words, "autological" is both autological and heterological depending on which set you place it in first because by being in that set, it belongs there, while "heterological" is neither autological nor heterological because if you place it in either set, it no longer belongs in that set.

Grelling and Nelson are credited with formulating this paradox in 1908, but it is sufficiently similar to "Russell's paradox," formulated by Bertrand Russell in 1901 and a Burali-Forti proof published in 1897 by Cesare Burali-Forti (which Russell subsequently showed was self-contradictory and thus a paradox, not a proof), that it is both an original and a derivative idea . . . making it a paradox paradox.

Before you say, "but this is just semantics," recognize that the Grelling–Nelson paradox has real world applications. For example the fact that light is both a particle and a wave, or that it is impossible to know both the location and speed of a particle (which might be acting like a wave).

Yes, but that's physics, you say. What does the Grelling–Nelson paradox have to do with the law? Plenty, because the attorneys are always compelled to operate in a world where things are both known and unknown. A person is presumed innocent until proven guilty, but innocent people are convicted at times and guilty ones go free even more often. We also have to deal with instances where a jury will convict a person of using a firearm during a felony, but acquit the same defendant of the underlying felony (if you don't practice criminal law, you should know that such a verdict is considered perfectly reasonable).

Judges are also not immune from the Grelling–Nelson paradox. For example, in a bench trial, a judge can find that an affirmative defense applies to a misdemeanor because the defendant has permissive immunity to perform the act that is otherwise criminal, but can still be convicted of a felony based on the same conduct.

Apart from being a distraction from more pressing matters at the end of a long week, why am I bringing up the Grelling–Nelson paradox? Because it is often the case that lawyers forget that just because something appears to be a thing, does not mean that it has to be that thing, nor is it always true that if our opponent is wrong about something, we are necessarily right. It's possible for a thing to have two different and opposing natures and its possible for opposing theories to both be wrong. If you become to wedded to the idea that you have the answer, you will never notice that it is the wrong answer, or not the only answer, or the right answer, just not for the question being asked..

So why was it safe for English Majors to read this without risking a deprivation of sleep? Because English Majors are sensible people who, rather than spending time trying to determine what can really be known about a universe where one thing can be itself and its opposite and its opposite can be neither itself nor its opposite, decide to read a good book instead and drift peacefully off to sleep . . . unless it's a real page-turner.

Comments